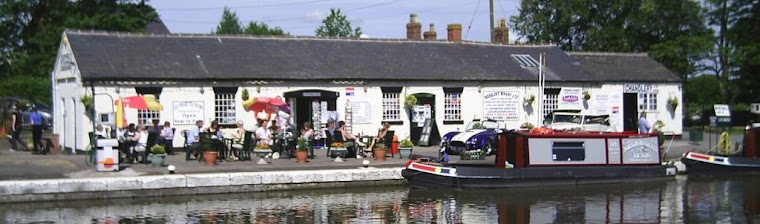

Simon Jenkins is a well known figure on the British canal system and has been a boater for decades, living on, working and owning boats and, for the last couple of decades, the managing director of Norbury Wharf on the Shropshire Union Canal.

Simon Jenkins and his partner Amanda

There he runs a brokerage, hire fleet, day boats, a trip boat and a chandlery, as well as a paint dock, dry dock and full engineering services. Simon has dipped his toe in to the waters of other boat-related ideas including sea-going charters, but the inland waterways are his first love and he has turned his gaze to Europe, with it’s wide waterways and fully functioning system of commercial river and canal navigations. He is just back from the boat buying trip of a lifetime, bringing his first historic barge back to Belgium, the country in which it was built, from the shores of the Mediterranean. Last month we told how he bought the barge and began the journey north from the Mediterranean. Now he is about the tackle the mighty Rhone. This is his story, in his own words.

We watched the flow rates intensively, knowing the river was higher and faster than most years, with the help of a very useful website giving all of the technical data for the river.

|

| Just leaving the Petite Rhone with the main river ahead |

Despite that, we had to make a decision and we made the choice that we would go. Now we were on the Petite Rhone before it joined the main Rhone river several kilometres further on. Once on the main channel we knew the worst section was a narrow bridge at Beaucaire.

After leaving the first lock the Petite Rhone seemed quite calm, not flowing especially fast giving me some comfort that this mighty river was a just pussy cat after all.Then we reached the confluence with the Rhone main river.

Gulp. This was no pussy cat, more of a raging Lion. It was massive and you could clearly see the swirls, the eddies, the whirlpools, as the current ripped onwards.

After leaving the first lock the Petite Rhone seemed quite calm, not flowing especially fast giving me some comfort that this mighty river was a just pussy cat after all.Then we reached the confluence with the Rhone main river.

Gulp. This was no pussy cat, more of a raging Lion. It was massive and you could clearly see the swirls, the eddies, the whirlpools, as the current ripped onwards.

Now, we could have turned back, but we carried on; this was clearly not going to be a gentle ‘walk in the park,’ although we took heart from the fact we had just passed another smaller barge heading upstream and at a much slower pace than ourselves.We thought if they can do it then so can we!

So we crossed the giant river and over to our side of the navigation as I didn’t want to meet anything big coming down the middle of the river, potentially doing over 20 kmph. This part of the Rhone is also used by big ships that don’t hang about, so it was important they we stay vigilant at all times.

So we crossed the giant river and over to our side of the navigation as I didn’t want to meet anything big coming down the middle of the river, potentially doing over 20 kmph. This part of the Rhone is also used by big ships that don’t hang about, so it was important they we stay vigilant at all times.

Our vessel has to have something called AIS which shows the position of our boat and means we can also see the position of other boats that have AIS. For boats over a certain length on the European inland waterways this is mandatory and, if I am honest, I wouldn’t venture on to a commercial waterway without it.

This device is a godsend as you can see ships well before they can be seen by eye and this gives you, and them, a chance to alter course to be safe and make best use of the river.

Boats over a certain size have to have something called a ‘blue board’ too, and/or an oscillating white light. This is to give approaching vessels a signal that you intend to pass their boat on the starboard side when normally it would be on the port side, especially useful when travelling against a flow and you need to take full advantage of the slack water which may be on the opposite side of the navigation channel.

The first time we were ‘blue boarded’ was a bit of a hair raiser, having never done it before, but once done and understood it was no problem, and we even did it to much larger vessels if it made sense for us to do so. We carried on against the flow, making very slow progress, around 7 kmph, until we could see the bridge at Beaucaire where we knew that the flow would be at its strongest.

This device is a godsend as you can see ships well before they can be seen by eye and this gives you, and them, a chance to alter course to be safe and make best use of the river.

Boats over a certain size have to have something called a ‘blue board’ too, and/or an oscillating white light. This is to give approaching vessels a signal that you intend to pass their boat on the starboard side when normally it would be on the port side, especially useful when travelling against a flow and you need to take full advantage of the slack water which may be on the opposite side of the navigation channel.

The first time we were ‘blue boarded’ was a bit of a hair raiser, having never done it before, but once done and understood it was no problem, and we even did it to much larger vessels if it made sense for us to do so. We carried on against the flow, making very slow progress, around 7 kmph, until we could see the bridge at Beaucaire where we knew that the flow would be at its strongest.

If anything went wrong as we were going through the bridge we could sink. if the engine had failed we would be swept sideways, pinned against the bridge abutments, capsize and sink. So it was a nerve racking few minutes as we entered the bridge.

I have it on video as it was quite dramatic, the speed reduced to just 2 kmph as we inched trough the bridge-the engine now on full power. All 160HP turning the giant four blade propeller, pushing the 130 ton barge against the flow of water.

I have it on video as it was quite dramatic, the speed reduced to just 2 kmph as we inched trough the bridge-the engine now on full power. All 160HP turning the giant four blade propeller, pushing the 130 ton barge against the flow of water.

The current was ripping past our vessel as we inched through at a snails pace, I was concerned that we would end up going backwards, fearing we hadn’t got enough power to push against the flow, but the old barge kept moving, ever so slowly, forward.

Then the speed started to increase kilometre by kilometre until we were back to our 7 kmph cruising speed, hugging the tree lined banks to stay in the slack water, looking for the shortest way around the bends to optimise the flow and shortest route - by no means an easy feat and requiring a lot of concentration.

In the next episode: Big locks, big boats and the problem with locks that generate electricity.

This series of articles can also be found in Towpath Talk newspaper every month this year.