ONWARDS

AND NORTHWARDS

|

| Simon and his partner Amanda |

Simon

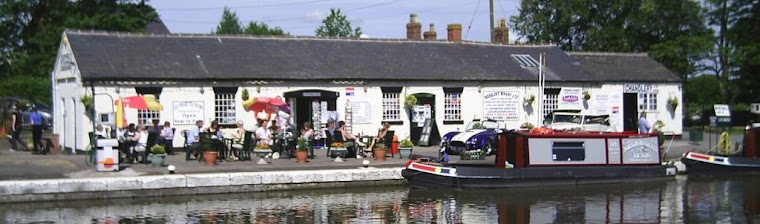

Jenkins is a well known figure on the British canal system and has

been a boater for decades, living on, working and owning boats and,

for the last couple of decades, the managing director of Norbury

Wharf on the Shropshire Union Canal.

There

he runs a brokerage, hire fleet, day boats, a trip boat and a

chandlery, as well as a paint dock, dry dock and full engineering

services. Simon has dipped his toe in to the waters of other

boat-related ideas including sea-going charters, but the inland

waterways are his first love and he has turned his gaze to Europe,

with it’s wide waterways and fully functioning system of commercial

river and canal navigations. He is just back from the boat buying

trip of a lifetime, bringing his first historic barge back to

Belgium, the country in which it was built, from the shores of the

Mediterranean. Last month he entered the mighty River Rhone and

braved the narrows. Now he is to meet some big locks and big boats.

This is his story, in his own words.

The

navigable river Rhone stretches from Lyon in central France to the

Mediterranean sea. It is 325km long and has 12 massive locks, it

travels along the Rhone valley through some spectacular places like

Avignon, Chateauneuf-du-Pape, Valence, Vienne, and Lyon.

|

| Wine country |

|

| Wine terraces |

As

well as being a very important commercial route it also plays an

important role in generating electricity in the form of hydro

electric power plants at every lock. The locks themselves are all

pretty much in canalised sections of the main river. These tend to be

narrower than the river and as they also have a hydro plant at the

end and this can mean even more strong currents.

We

had to pick our timings, as best we could, to avoid peak generating

times – morning, lunch and evening - when the plants could be

operating at maximum potential.

This

means letting a tremendous amount of water through the generators,

slowing our progress down to 4 or 5 kmph, grindingly slow, and always

a relief to get in to the lock.

|

| Hydro-electric generation plant at a Rhone lock |

The

biggest lock we did was Bollene lock, measuring a massive 190 m long,

and 12 m wide, with an impressive drop of 23 m. As we were going

uphill I think we got the best and most impressive view. It was like

a cathedral of locks, a massive, cold and a dank damp place to be.

As

we entered the lock we made our way on our, now apparently tiny

little boat, towards the front, secured our lines to the massive

floating bollards sunk in to the lock walls and waited.

|

| Bollene lock |

|

| Entering the lock |

|

| Big gates |

As

I looked back out of the wheel house I was greeted by the width of

the lock starting to fill with a hotel ship, its huge bow and beam

occupying the lock with inches to spare.

It

loomed up on us and almost over hung the stern of our boat. We were

close enough to speak with some of the guests onboard who were just

finishing breakfast. As they looked down on us we must have seemed

like ants on a bit of a branch clinging to the lock sides.

The

lock was very gentle as it filled, and in no time at all we were all

at the top, gates open, green lights and off we go again.

|

| Hotel ship entering behind us |

|

| Hotel ship goes on its way |

There

are not that many places to stop along the river - but there were

some fascinating places we would love to have lingered. However, as

we were on a schedule on our journey we couldn't take advantage and

most nights we ended up moored above a lock.

Not

ideal moorings, as they were mostly on what is called ‘dolphins’

which are bloody great steel tubes sunk in to the bed of the river,

some without any shore access. As the commercial boats could work 24

hours a day, the wash from them made for an unpleasant nights sleep,

with the ropes creaking and heaving as loaded barges and hotel ships

went past.

We

eventually made the last narrow point of our journey at a place

called the Medeterean bridge at Givors, which was also one of the

longest lock cuts, or diversions as they are also known, on our

route.

We

had been watching the flow rates increase day by day as the North had

rain and the snow in the Alps kept melting. As we were travelling

North things were getting quite bad and there was even the prospect

that we could have been stuck on the river, as it could be closed to

navigation for safety reasons.

By

now there was plenty of flotsam and jetsam coming down the brown and

dirty river so we tied up on a handy pontoon just before the bridge

and decided to wait 24 hours to see if the flow would subside a

little.

I

phoned and spoke with the previous owner and he said that he would

never have attempted to go through that bridge with the flow as

strong as it was, even though he had confidence in the boat being

able to do it.

We

waited 24hours with the rushing water around our bows-and the flotsam

and jetsam getting caught under the pontoon. I was starting to get

concerned as we watched big commercial barges and hotel boats come

past us sideways around the bends, taking up the entire width of the

river at up to 20 kmph, and then the very rare barge pushing against

the flow at 5 kmph.

|

| Large pusher tug on the fast-flowing Rhone |

|

| Tug without its barges |

In

the end, that little barge that we had overtaken right at the start

of our journey on the Petite Rhone came chugging past us. We watched

him for about half an hour as he pushed against the flow.

Paul

radioed the guy who turned out to be Dutch, he said that he had done

this journey several times and, although the flow was stronger than

normal, he was happy enough to push on.

|

| Small barge pushing the flow |

I

had total confidence in our barge and the engine, so the decision was

made, and we set off shortly afterwards. We untied from the pontoon

and crabbed out sideways and in to the flow of the river.

We

maintained 4 or 5 kmph all the way until the lock came in to view and

we slipped inside our last lock on the River Rhone. Not being

foolhardy, and having experienced just what a powerful river we were

navigating, we all had lifejackets available, and we had two half ton

anchors ready to be deployed in an emergency. You don’t tackle

these conditions lightly!

In

the next episode: Thousands of litres of diesel, boarded by armed

police and a stoppage forces a route change.